U.S. Supreme Court hears arguments in Permian Basin nuclear waste case

Adrian Hedden

Carlsbad Current-Argus

achedden@currentargus.com

Stalled plans to store spent nuclear fuel in the Permian Basin could get new life depending on how the U.S. Supreme Court rules in a case seeking to restore vacated licenses for two such facilities.

The court heard oral arguments in the case March 5 and filed it for a later decision

At issue are two projects to temporarily store spent nuclear fuel rods – one proposed by Holtec International near the Eddy-Lea county line in southeast New Mexico and another proposed by Interim Storage Partners in Andrews, Texas, about an hour’s drive east.

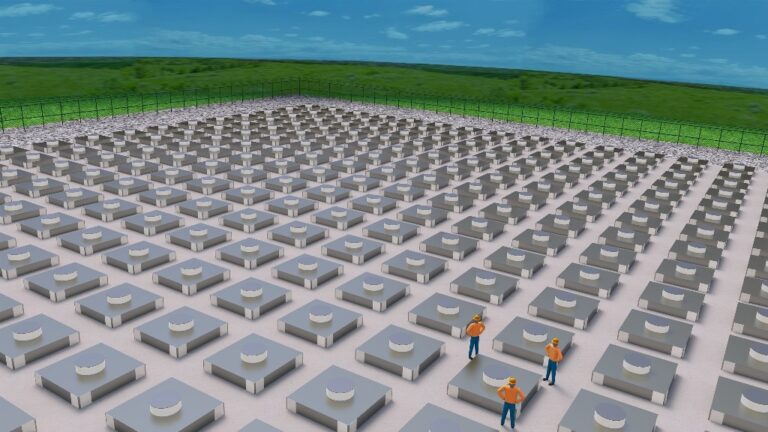

Holtec’s plan calls for a newly constructed facility to hold up to 100,000 metric tons of the rods. The Texas project would augment the existing Waste Control Specialists facility in Andrews to store about 40,000 metric tons of the materials.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission granted the Texas site a license in 2021 and approved a license for Holtec’s project in 2023, but the licenses were vacated in separate 2023 decisions by the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. The court said the licenses were invalid under a provision of the federal Atomic Energy Act that specifies spent nuclear fuel can only be moved to a permanent, deep geological repository.

Those rulings were appealed last year to the Supreme Court in separate fillings by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the companies. The appeals were consolidated, meaning any ruling on the Texas case will also apply to the New Mexico proposal.

Attorneys from Interim Storage Partners and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission argued to the Supreme Court that the facilities were legally licensed by the federal agency and would provide a solution to the nation’s problem of what to do with its nuclear waste.

The state of Texas and oil and gas company Fasken Oil and Ranch both appealed the NRC’s original approval of the license for Interim Storage Partners and now want the Supreme Court to affirm the circuit court’s revocation of the license, arguing that the projects in the Permian Basin pose too big a risk for the local area.

What is temporary?

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch voiced some of the same concerns, asking how the facility could be considered “temporary” when the license was for 40 years of operations.

He pointed to canceled plans for a permanent repository at Yucca Mountain, Nevada, which was defunded by the administration of President Barack Obama after officials from that state opposed the project.

Gorsuch also voiced concerns about impacts the site could have on the oil and gas industry that is booming in the region where the facilities would be built.

“Yucca Mountain was supposed to be the solution. We spent $15 billion. It’s a hole in the ground. How is this interim storage that the government is authorizing here, especially when ISP is getting a 40-year license. That doesn’t sound interim to me,” Gorsuch said. “On a concrete platform in the Permian Basin where we get our oil and gas? Hopefully, we don’t get irradiated oil and gas.”

Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor said that by not moving the spent fuel, which in many cases sits at the site of decommissioned nuclear reactors, the federal government continues to put local communities at risk.

“If it takes 40 or 80 years to have a solution, it is still temporary,” Sotomayor said. “The risks to communities continue to rise If we keep permitting storage in facilities that have had to be shut down.”

David Frederick, an attorney for Fasken, argued the material was safer where it was, stored in cooling pools that gradually lower the heat and danger posed by the fuel rods than it would be while being moved by rail to rural New Mexico.

“That material is so hot, it takes years to cool,” he said. “It can only be done safely onsite by removing the reactor core and moving it into water.”

Malcom Stewart, a Justice Department lawyer representing the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, said many of the former power plants now only functioned to store the waste left after decommissioning.

He said moving the rods to one location – in the desert of the Permian Basin – would allow the former plant locations to be repurposed and restored to their native state.

“The petitioners and ISP have argued that you have a bunch of places around the country that now serve no other purpose than to store spent nuclear fuel, and it would be better to centralize the waste so that the other facilities can be returned to what is called green space,” Stewart said.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said the federal government already decided that Interim Storage Partners could move and store the rods safely, contending that future advancement in technology could make it even safer.

“We have (Interim Storage Partners) here saying that they can receive this material. I’m not fully understanding why it matters that the material is so hot in a situation where the commission has licensed this transfer,” Jackson said. “Someone thinks it can be done.”

But attorney Aaron Lloyd Nielson of the Texas Office of the Attorney General argued that regardless of how it is moved and stored, and the level of safety, the facility would pose decades of risk and potentially be a target for foreign adversaries.

“If anyone thinks this is temporary, I have a bridge to sell you. There is no way we can move all the spent fuel in 60 years,” he said. “What the commission has done is put an enormous terrorist bullseye on the Permian Basin.”